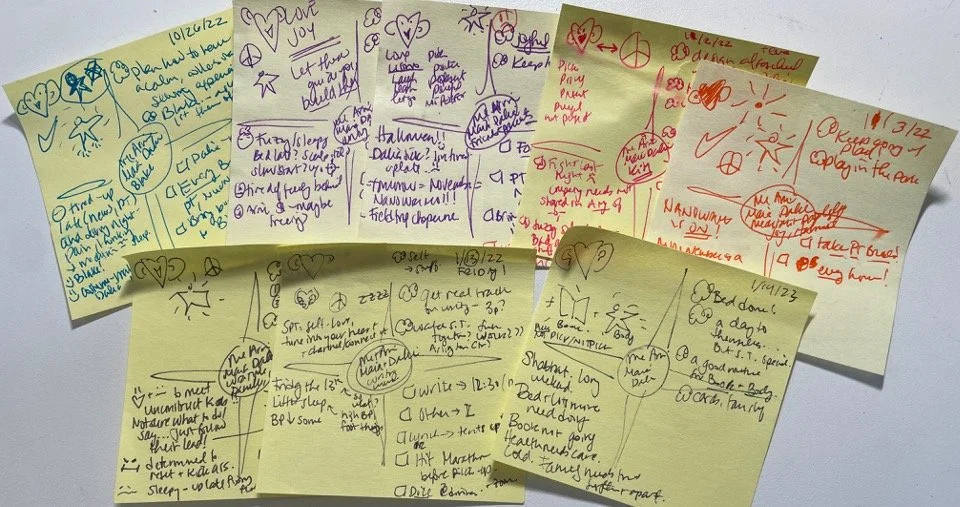

As I drafted my Fall 2025 newsletter, coming out for Thanksgiving—the 20th edition, and 5th anniversary of the first grateful newsletter I posted at Thanksgiving 2020—the scene on the floor next to me caught my eye, and I had to capture it for you.

I love seeing how my younger daughter’s work (on a middle school history project) and mine intertwine. In the foreground, you can see both of our scrap piles, working toward the outcomes further away. To the other side, on our not-pictured shared workbench, my older daughter’s steadily-growing experiments hand-painting pins made from bottle caps crimped over can tabs.

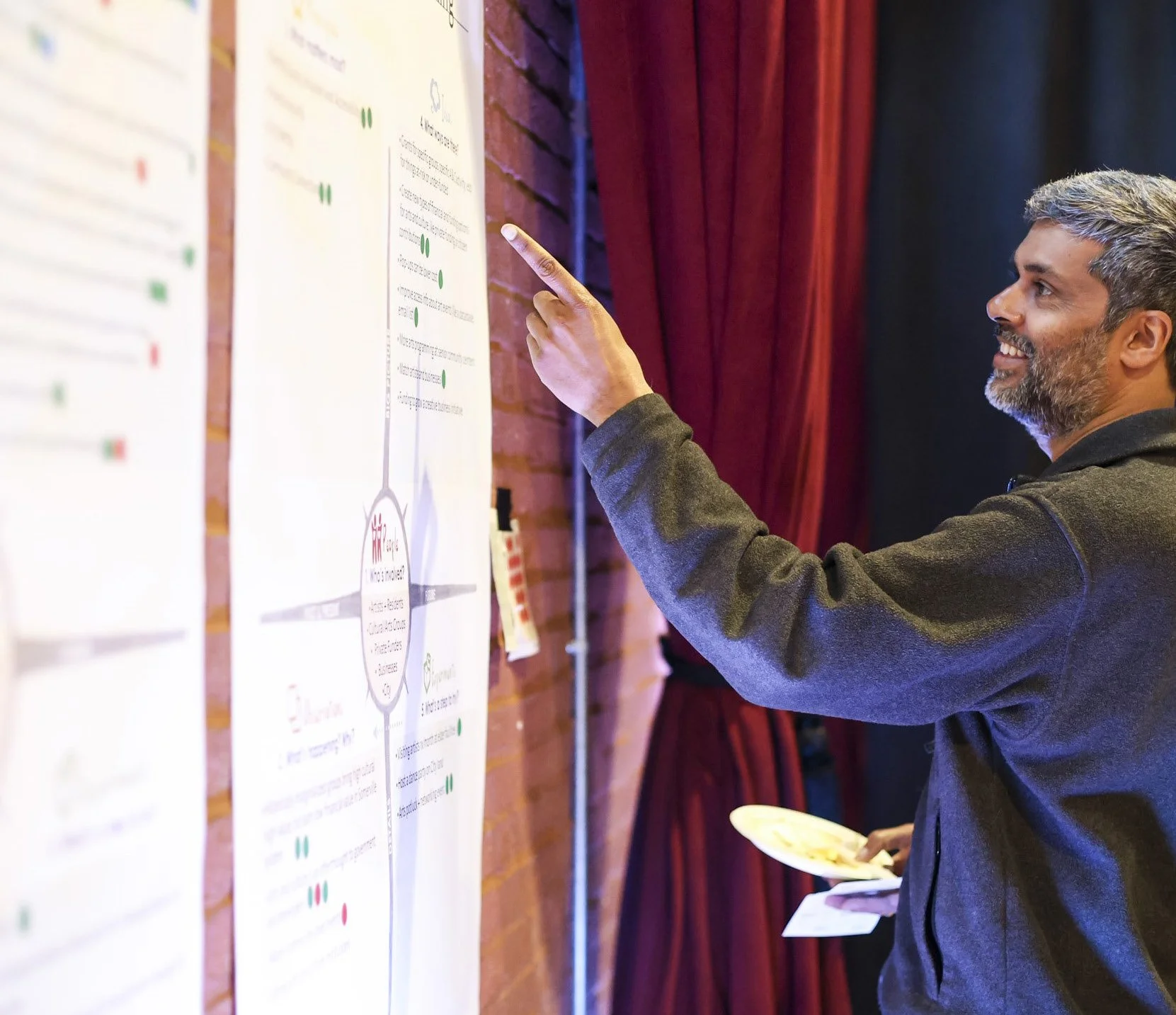

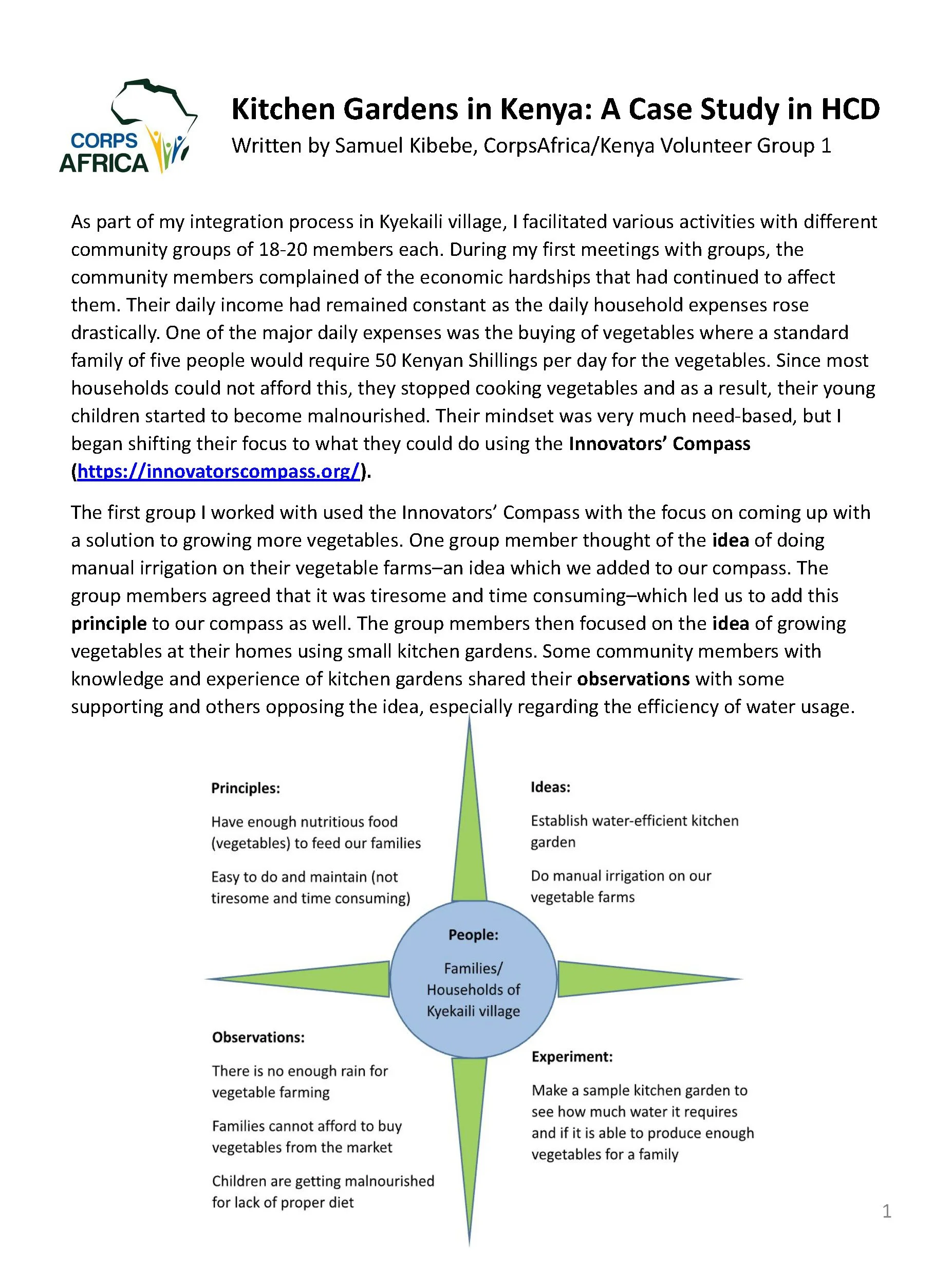

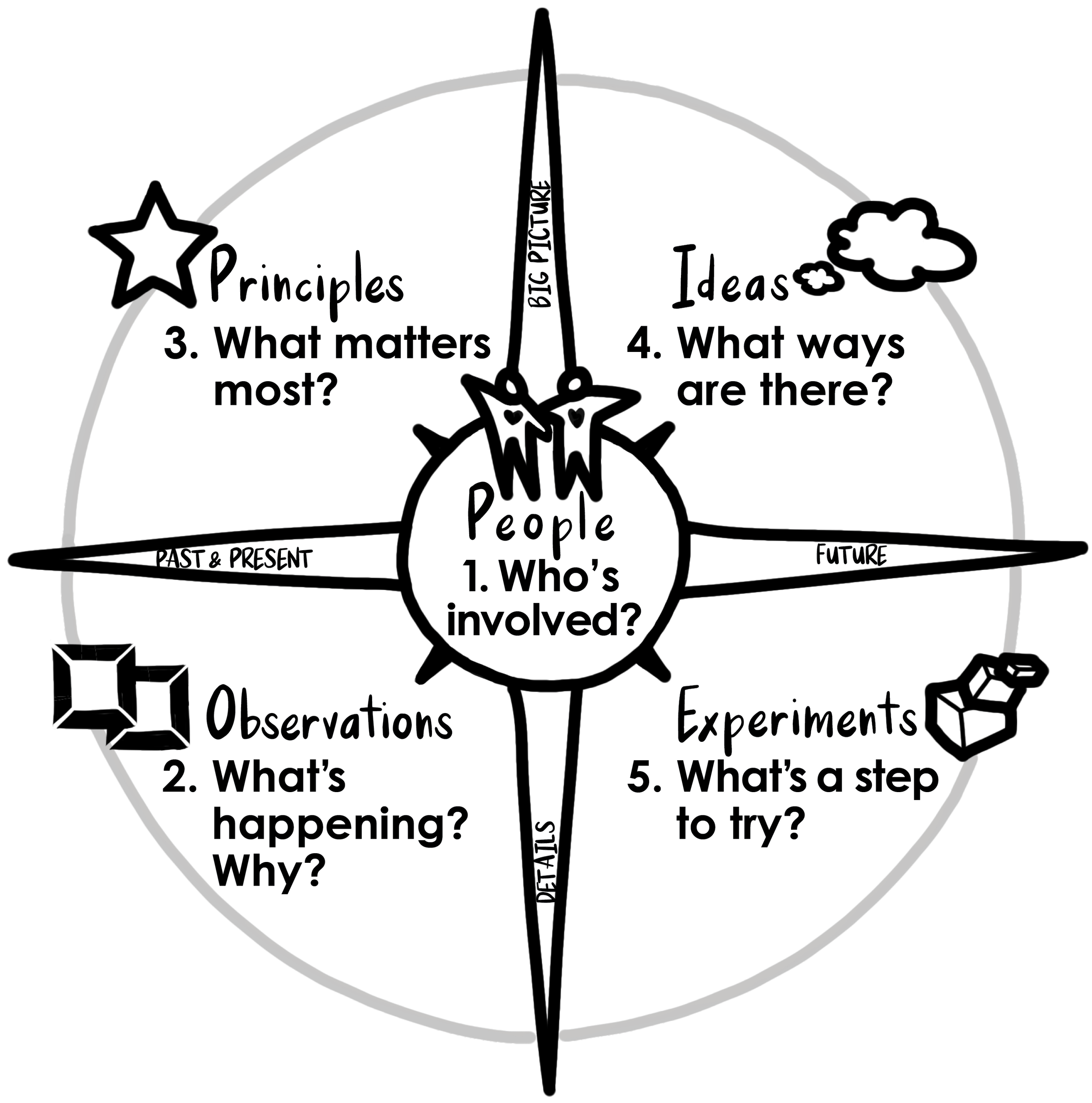

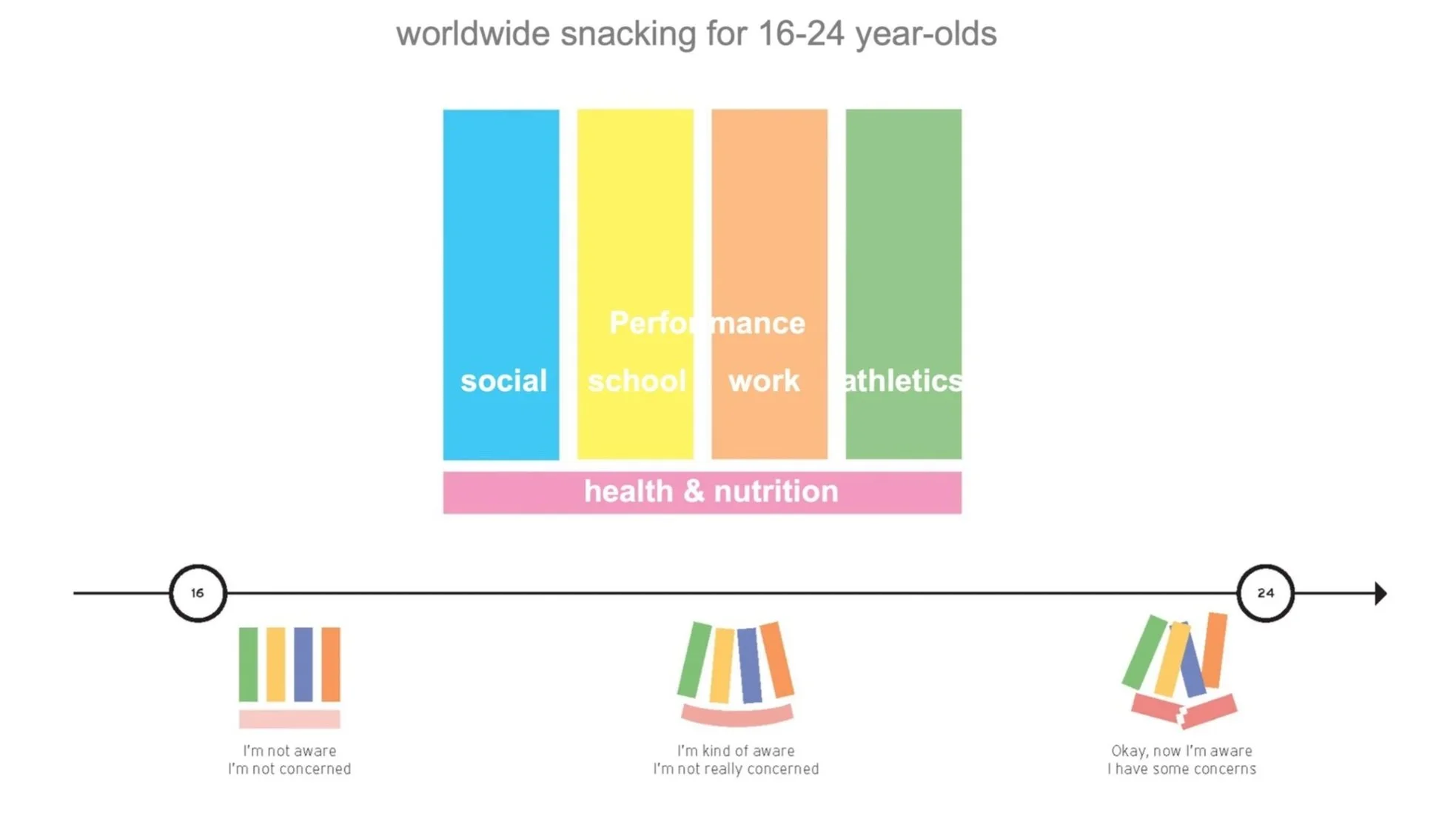

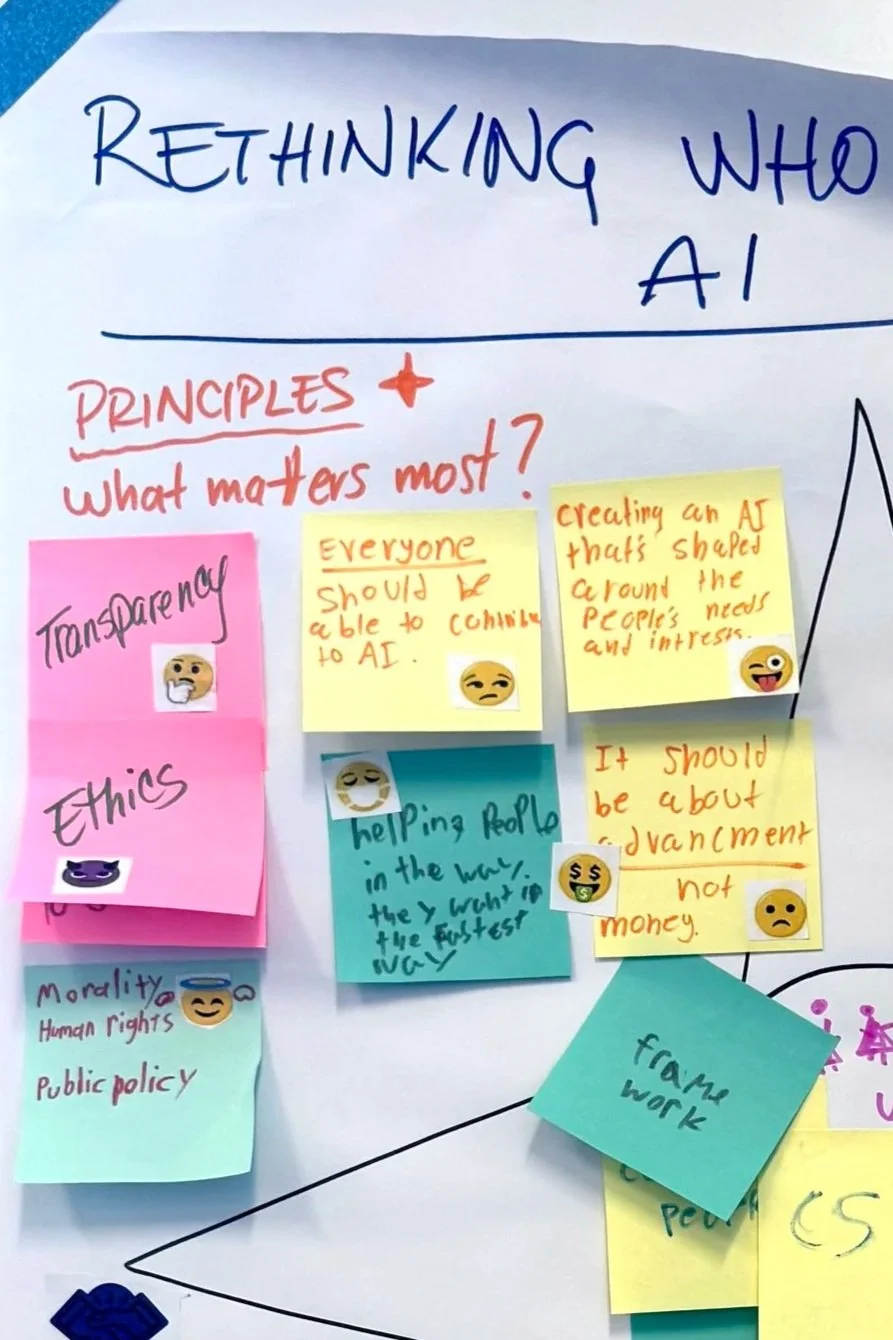

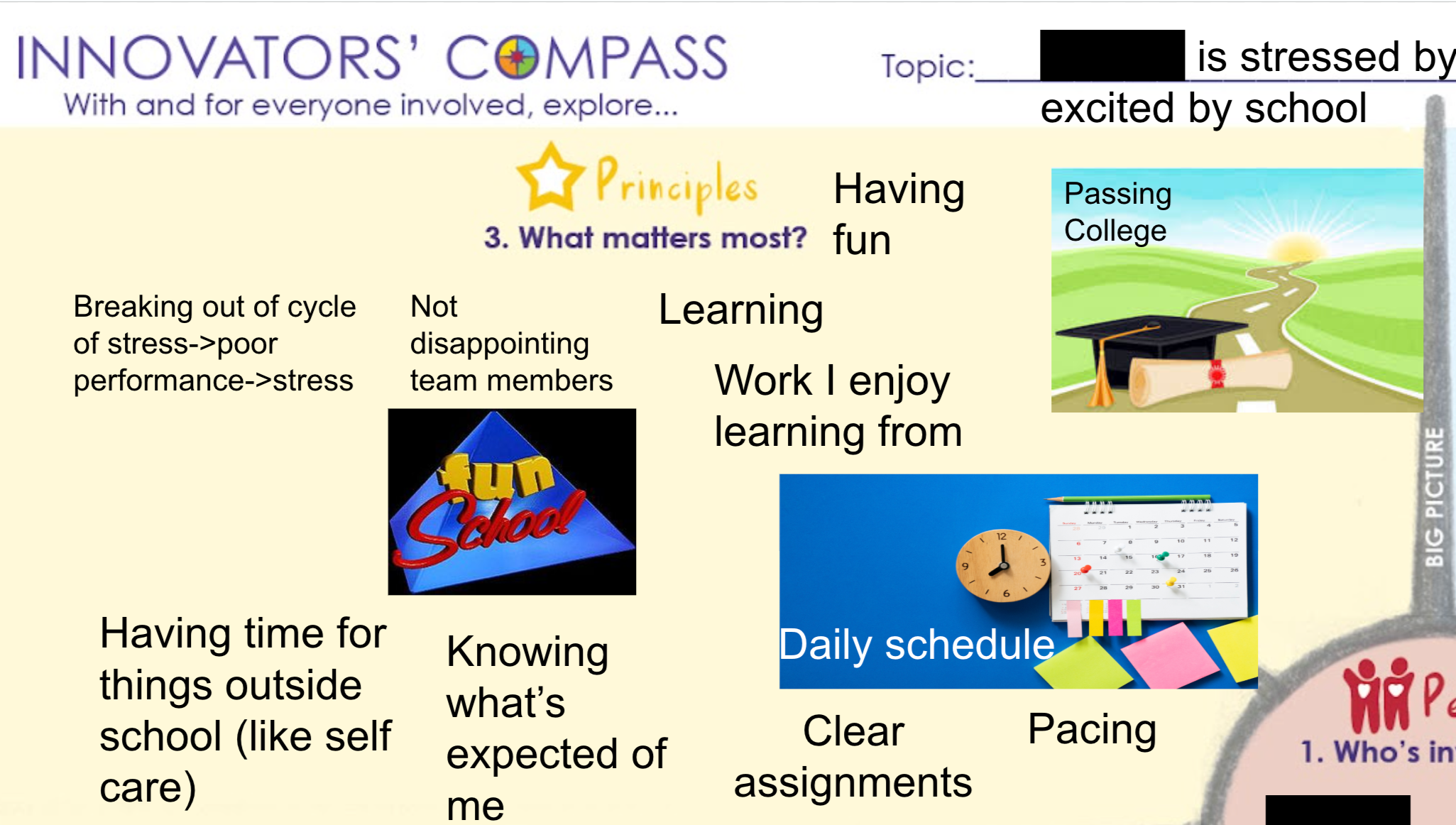

It occurred to me to finally share a bit of how “the sausage”—the most powerful and accessible tools for making things better and less stuck in our lives, work, and world that I can muster—gets made from all of the observations and ideas that people share. Those people range from readers of my newsletter, to participants in all my workshops and coaching, to the unwitting taxi drivers and fellow parents who share their life conundrums with me—to the many, many using innovatorscompass.org tools around the world.

I add theirs to my own observations and ideas sparked from podcasts, books, and practices across every spectrum of work and life, and my personal day-to-day experiences. As I reflact on those experiences, I obsessively seek the guiding principles and next experiments for my work, whether I draw out a physical Compass or not.

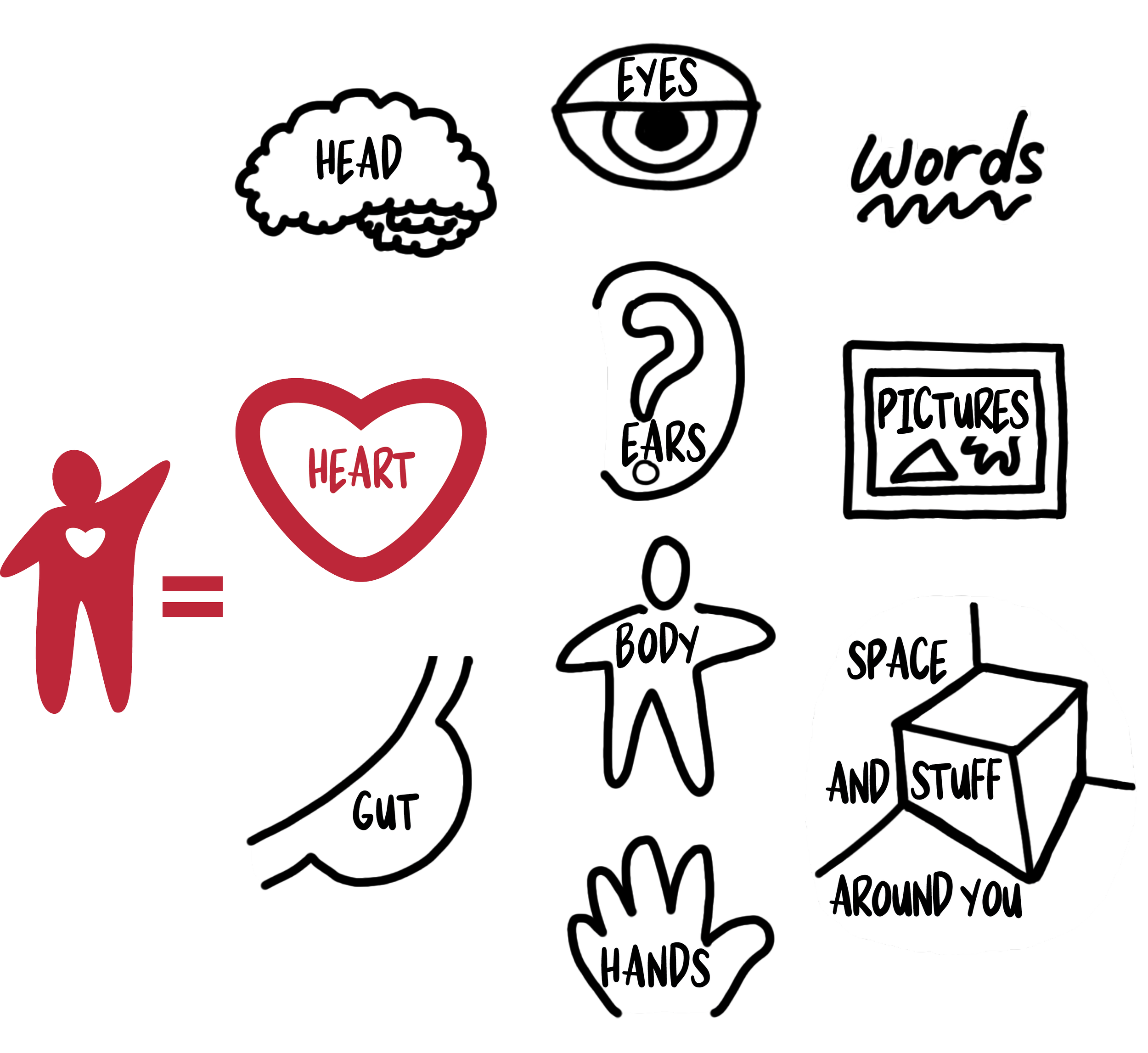

Now I blend in the weird superpower that emerged in my 13 years at the innovation firm IDEO (we all have them, if you haven’t found yours, join one of my free Weekly Online Workshops or Chapter 4 of my book when it comes out :). That superpower is connecting diverse information and ideas through pictures, as simple as possible, that people can immediately understand and use to decide, design, whatever they need to do. Also not pictured here are the sketches that preceded these printed experiments—lots of sketches.

I always come away with different variations, unsure of which would be more effective, so I identify the key questions behind those decisions and make experimental versions to explore those.

First, I make these for myself. Once they’re in physical form, I can engage with them in different ways—glance them from a distance, try actually using them, and so on, to catch anything I want to change.

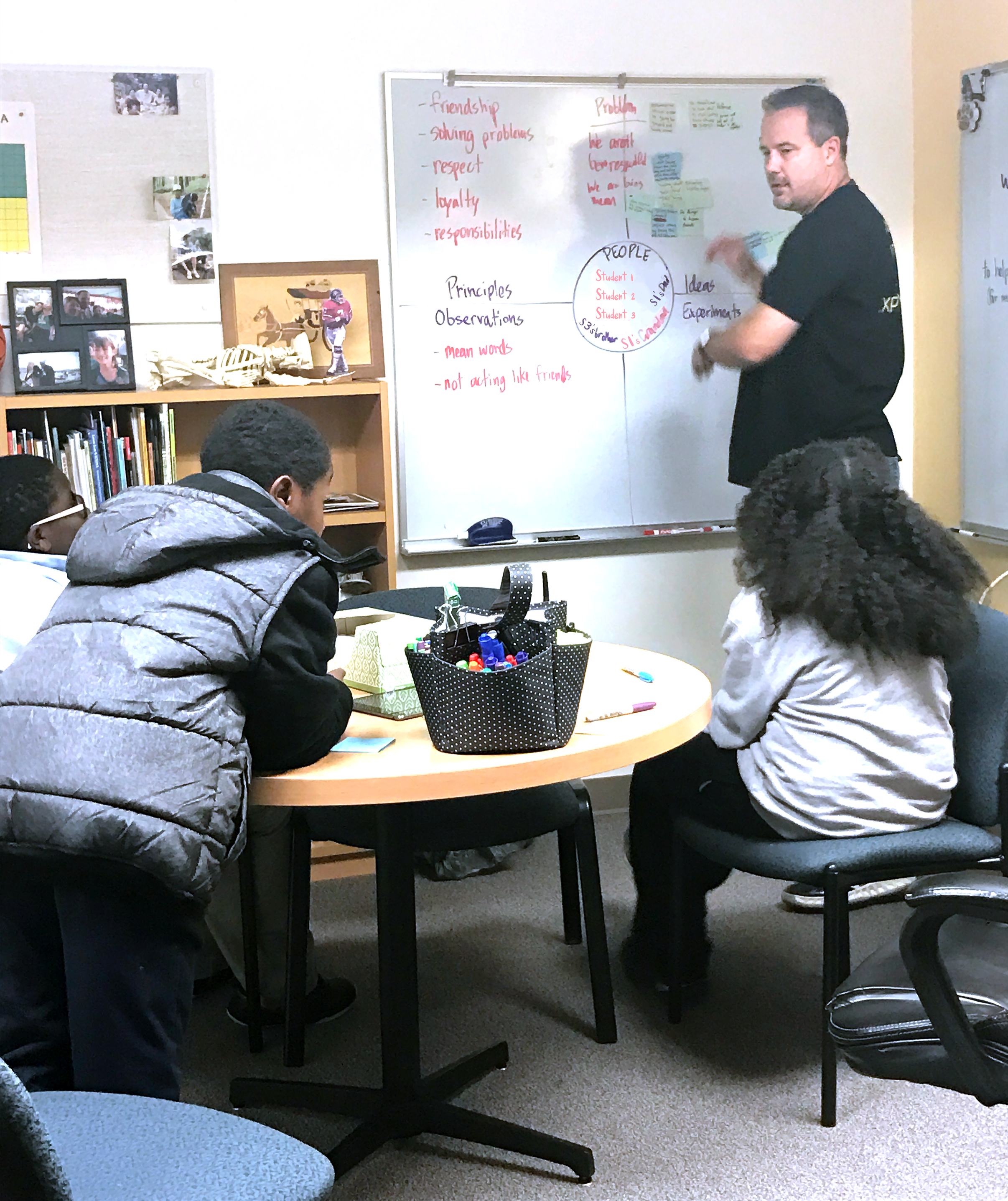

Then I try them on innocent bystanders who happen to find themselves in the same physical room with me (like my daughters, whose feedback often comes sprinkled with a healthy dose of teasing or sarcasm) or a shared Zoom room (like my regular groups of fellow writers, design educators in higher education, and IDEO alumnae). And, with saint-like regular helpers—endless gratitude to Daniel Koff for his always-enthusiastic yet honest and insightful input on the original Compass and so, so many diffferent tools and iterations thereof since, and to Kim Zajac—not only for ideas she’s contributed for Compass tools (like the postcards) but also, when my old printer gave out, for one that as she said, just prints and prints without quitting or running out of ink! This work wouldn’t exist without all those contributions!

What survives this tool-design Darwinism arrives, voila, in your next newsletter, workshop, coaching call, or taxi ride with me!

As I turn to writing a book, obviously, some things will need to settle after a decade of dedicated, relentless iteration. But I’ll never stop striving to find the biggest difference we can make with the simplest prompt or picture that can slip into any situation in our lives, work, and world.

This Thanksgiving, I’m grateful to all of you on that ongoing journey with me.